Please E-mail suggested additions, comments and/or corrections to Kent@MoreLaw.Com.

Help support the publication of case reports on MoreLaw

Date: 04-26-2018

Case Style:

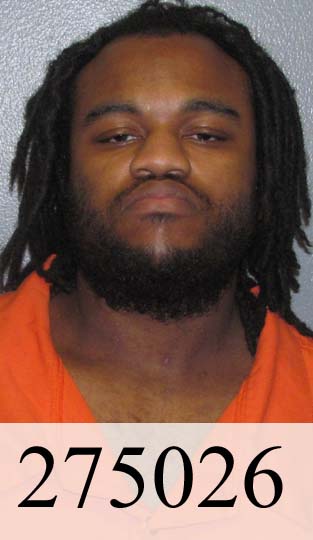

RAKIM MOBERLY V. COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY

|

Case Number: 2016-SC-000429-DG

Judge: Daniel Venters

Court: Kentucky Supreme Court

Plaintiff's Attorney: Andy Beshear

Attorney General of Kentucky

James Daryl Havey

Assistant Attorney Gen~ral

7

Defendant's Attorney: Brandon Neil Jewell

Assistant Public Advocate

Description: Lexington Police Officer Roman Sorrell was following a vehicle in the very

early hours of a December morning. He performed a registration check on the

vehicle license number and discovered that the vehicle's registration had been

cancelled because it had no liability insurance coverage. Sorrell initiated a

traffic stop of the vehide at 3':35 a.m. Appellant was driving the vehicle.

At Sorrell's request, Appellant provided his driver's license. He told

Sorrell that the car was not his an& that he could not provide proof of

insurance.~. Sorrell described Appellant as fully cooperative but abnormally

nervous .and sw~ating at the brow. Appellant was .smoking a cigarette and

blowing the smoke into the vehicle's interior. He kept looking toward the right

side of the car.

Sorrell took Appellant's d_river's license back to his cruiser and began

writing .the traffic citation. He also spent about five minutes accessing a jail

website and a police database to find out more information about Appellant.

That inquiry disclosed that Appellant had been charged previously with

trafficking in marijuana and carrying a concealed deadly weapon; it did not . r.

indicate whether Appellant had been convicted of these charges.

Sorrell returned to Appellant's vehicle. He told Appellant that he knew

about the prior charges.. He asked if Appell~t had drugs or weapons· in the

vehicle. Appellant said lie did not. Sorrell asked for consent to search the

2

vehicle, and Appellant declined. Sorrell acknowledged that at that point in the

usual traffic stop, he would have given the driver a citation and let him leave.

However, because Appellap.t seemed nervous, was sweating, blew his cigarette

smoke into the vehicle instead of toward the officer," kept looking to the right

\_ side of the car, and had prior charges, Sorrell decided that he would detain

Appellant further while he called for a canine unit to conduct a sniff search of

the vehicle .

. The canine handler, Officer Jones, arrived with the dog within a few

minutes. After speaking to Sorrell and Appellant, Jones retrieved the dog and

conducted a sniff search of the car. The dog alerted to indicate the presence of

drugs on the driver's side of the vehicle.

Sorrell and yet another officer who had arrived on the scene then

searched Appellant's vehicle. In the~glove compartment (not on the driver's ' side of the car as the dog indicated), they found a cigarette box containi!1g

cocaine and methylone, a controlled subs~ce they thought was heroin .. They

also found a handgun under the driver's seat. Appellant was arrested at 4:20

a.m., some forty-five minutes after the initial stop.

Appellant was indicted on two counts of trafficking in a controlled_

substance (heroinl and cocaine); receiving stolen property (the firearm); and

carrying a· concealed deadly weapon. He moved to suppress the incriminating

~ I This charge was amended to trafficking in a controlled substance, second degree. ·

3

(

evidence on the basis that he was detained by the sniff search beyond the time

reasonably required to complete the traffic stop.

After the trial court denied the suppression motion, Appellant preserved

his right to appeal by entering a conditional guilty plea to one count of

possession of a controlled sub~tance, first degree, cocaine, and carrying a

concealed deadly weapon. The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court's

denial of Appellant's motion to suppress. We granted discretionary review.

II. ANALYSIS

When reviewing a trial court's ruling on a motiop. to suppress, the

findings of fact are reviewed under a clearly erroneous standard, and the

conclusions of law are reviewed de novo. Davis v. Commonwe,alth, 484 S.W.3d

288, 290 (Ky. 2016) (citations omitted). Since the parties do not challenge the

trial court's findings of fact, we tum our attentl.on to the trial court's

conclusions of law.

The trial court concluded, and no one disputes, that the initial traffic

stop was justified when Sorrell obtained information indicating that the vehicle

was uninsured. Wilson v. Commonwealth, 37 S.W.3d 745, 749 (Ky'. 2001) ("[A]n

officer who has probable cause to believe a civil traffic violation has occurred

may stop a vehicle regardless of his or her subj~ctive motivation in doing so.").

The triai court also acknowledged our holding in Commonwealth v.

Bucalo, 422 S.W.3d 253, 258 (Ky. 2013), that a lawful traffic stop may

nevertheless violate an individual's Fourth Amendment rights

4

'if its manner of execution unreasonably infringes interests protected by the Constitution'2 or it 'last[s] longer than is necessary to effectuate the purpose of the stop. '3 Generally, if an officer unreasonably prolongs the investigatory stop in order to facilitate a dog sniff, any resulting seizure will be deemed unconstitutional.

We also said in Bucalo that a traffic stop may be prolonged beyond the

time required to effectuate the purpose of _the stop when additional information

properly obtained during the stop provides the officer with a reasonable and

articulable suspicion that other criminal activity is afoot. Id. at 259 (citing

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 30 (1968)).

At the time of its ruling, the trial court did not have the benefit of the

Supreme Court's more recent statement on this issue in Rodriguez v. United

States, 135 S. Ct. 1609 (2015), nor did it have our post-Rodriguez decision, \. Davis v. Commonwealth, 484 S.W.3d 288 (Ky. 2016). Davis and Rodriguez

involved the increasingly common scenario we see here: a police officer

ostensibly stops a vehicle for an observed traffic violation but also harbors

suspicions of criminal drug activity inadequate to justify a search. A drug dog

arrives'on the scene within minutes to conduct a sniff search concurrently with

the traffic stop. Rodriguez highlighted and clarified several principles relevant

to this scenario. L

First, the Fourth Amendment tolerates certain unrelated investigations

conducted during a routine traffic stop as long as they do not lengthen the

2 Quoting fllinois v. Caballes, 543 U.S. 405, 407 (2005).

3 Quoting Florida v. Royer, 460 U.S. 491, 500 (1983).

5

roadside detention. The traffic stop may not be prolonged beyond the point ·

reasonably required to complete the stop's mission. Otherwise, the stop

constitutes an unreasonable seizure. 135 S. Ct. at 1614-1615,

Second, "[a]uthority for the seizure [of the vehicle and the driver] ends

when tasks tied to the traffic infraction are-or reason~bly should have been

completed." Id. at 1614. ·"[I]n determining the reasonable duration of a stop, 'it

I [is] appropriate to examine whether the police diligently pursued [the]

investigation."' Id. (quoting United States v. Sharpe, 470 U._S. 675, 686 (1985)).

More significantly, however, Rodriguez addressed the burgeoning

question.of whether prolonging the stop for a "de minimis" time to conduct

additional investigation unrelated to the purpose of the initial stop would be

regarded as constitutionally significant. The Rodriguez Court noted that

officers\may slightly extend the stop with "certain negligibly burdensome

precautions" needed to assure their safety. Id. at 1616. No constitutional

violation occurs because those precautionruy measures are directly connected

to the mission of the initial' traffic stop. "On-scene investigation into other

crimes, however, detours from that mission." Id. The Court specifically noted

that a dog sniff search to find drugs lacks a close connection to the legitimate . . - . purpose of the traffic stop; the sniff search "is no_t fairly characterized as part of

the officer's traffic mission." Id. at 1615. \ . In short, in Rodriguez the Supreme Court issued a blunt rejection of the argument that a "de minimis'' extension of the time taken for the stop does not

offend the Fourth Amendment:

6

/

As we said in Caballes and reiterate today, a traffic stop 'prolonged beyond' that point is 'unlawful.' The critical question, then, is not whether the dog sniff occurs before or after the officer issues a ticket, ... but whether conducting the sniff 'prolongs'-i.e., adds time to-'the stop.'

Id. at 1616 (internal citations omitted).

' Applying Rodriguez, we held in Davis v. Commonwealth that "any

prolonging of the stop beyond its original purpose is unreasonable and

unjustified; there is no 'de·minimis exception' to the rule that a traffic stop

cannot be prolonged for reasons unrelated to the purpose of the stop." 484

S.W.3d at 294.

Appellant concedes that the initial traffic stop was valid, but he contends

that the stop was .unconstitutionally prolOnged on two occasions. First, he

argues that Sorrell's legitimate mission-· issuing traffic citations for the vehicle

registration and insurance violations-was impermissibly extended without

good cause when Sorrell diverted his attention from writing the traffic citation

and spe~t several minutes searching online databases for information

pertaining to Appellant

Second, Appellant contends that, even if Sorrell's time spent searching

the online databases was part of his diligent pursuit of the traffic 'citation,

deferring the traffic citation to call in the canine unit and waiting for the dog

sniff unconstitutionally prolonged his detention.

We note at th'.is point that Rodriguez identifies as one of the routine tasks ' associated with a proper traffic stop a check for any outstanding warrants that

may be pending against the driver. 135 S. Ct. at 1615 (citing Caballes, 543

7

I

/

U.S. at 408; Delaware v. Prouse, 440 U.S. at 658-660 (1979); 4 W. LaFave, r ,..--- Search and Seizure§ 9.3(c), pp. 507-517 (5th ed. 2012)). The officer did not

clearly identify the "jail website," but he admitted that it only provides a

"charge record." He said: "J d_on't have access to convictions." He described the

police database as "AS-400" and as containing more detailed h;1formation-than

the jrul website, but he makes no reference to outstanding warrants.

Significantly, the officer never says that he used these websites to see if

Appellant was wanted on outstanding warrants, and the Commonwealth never

argues that the officer spent any time at all checking for outstanding warrants.

Nevertheless, we will indulge in the presumption that at least a portion of the

officer's time spent on the online sites can be justified as a check for

outstanding warrants, although the Commonwealth does not assert as much.

Faced with a silent record, we can presume no more.

The·trial court acknowledged that Sorrell's justification for delaying the

traffic citation to search computer databases wa~ "certainly not ovei-Whelming,"

but concluded that Appellant's nervousness and sweaty brow at 3:30 a.m. and

"blowing smoke in a rather strange way'' justified an extension of the stop to

conduct the additional investigation on the computer.

Next, the trial court acknowledged that calling in a canine search was "a

little bit unusual when you get stopped for no license tag, no valid license tag,

and just having no insu_rance." Nevertheless, the trial court concluded that the

fact that Appellant was nervous, sweating, and blowing smoke in the car, and

additionally :Q.ad "~harges of carrying a concealed deadly weapon and

8

I

,_

marijuana," established reasonable and articulable suspicion to justify the

prolonged detention of Appellant until the dog could arrive and complete his

search.

The Court of Appeals agreed, concluding that after seeing Appellant and

getting his driver's license, Sorrell had reasonable and articulable suspicion to

return to the cruiser and check for Appellant's name on computer databases

because Appellant: 1) was nervous; 2) had sweat on his brow; 3) was blowing

cigarette smoke toward the car's interior; and 4) was looking around and over'

his shoulder.

The Commonwealth agrees that Sorrell extended the traffic stop beyond

the time necessary to resolve the traffic violation. The question is whether the

officer had a reasonablerarticulable suspicion of other ongoing illegal activity

when he prolonged the stop for the time needed to retrieve the dog and conduct

the sniff search. We consider the totality of the circumstances to determine

whether a particularized and objective basis existed for suspecting Appellant of

illegal activity. United States v. Cortez, 449 U.S. 411, 417 (1981). · . '

When assessing the totality of the circumstances relevant to a Fourth

Amendment claim, there is a "demand for specificity in the information upon . '

which police .action is predicated." Terry, 392 U.S. at 22 n.18. We consider the

information from which a trained officer makes inferences, such as objective

(• observations and the method of-operation of certain.,kinds of criminals, and

r whether that information yields a particularized suspicion that the particular

individual being stopped"is engaged in wrongdoing . . Cortez, 449 U.S. at 417

9

418. Due weight is given to specific reasonable inferences. Terry, 392 U.S. at

27. Although this "process does not deal with hard certainties, but with

probabilities," Cortez, 449 U.S at 418, a reasonable suspicion is more than an

,unparticularized 'suspicion or hunch, Terry, 392 U.S. at 27.

Appellant argues that the circumstances cited by the Commonwealth as

justific.ation for prolonging the traffic stop neither individually nor collectively

give rise to a reasonable suspicion that he was involved in any criminal activity.

He cites Strange v. Commonwealth, 269 S.W.3d 847, 851 (KY:. 2008), and

Commonwealth v. Sanders, 332 S.W.3d 739, 741 (Ky. App. 2011), as analogous

cases in which this Court and the Court of Appeals respectively found that the

circumstances were insufficient to establish reasonable suspicion of criminal

activity. In Strange, the suspect stood late at night in a public area kriown for

criminal activity near a public pay phone that had been occasionally used for

drug transactions. As officers approached, he walked quickly to a van parked

nearby. We rejected the notion that being present in a high crime area at

night, near a pay phone, apparently opting to avoid police contact suggested

criminal activity. The fact is that many honest, decent, law-abiding citizens

live in high-crime areas under similar circumstances and would behave the

same way. We held that there was insufficient evidence to justify an

investigatory stop and seizure. In Sanders, the suspect was a pedestrian out

late in a neighborhood known for drug activity. She was seen following

someone, and sometime later, she returned to the street walking in the

opposite direction and she appeared nervous. The Court of Appeals concluded '·

10

that these factors did not give rise to reasonable suspicion that the pedestrian

was involved in criminal activity.

The Commonwealth concedes that none of the individual factors of

. . Appellant's conduct would arouse a reasonable suspicion, but it argues that

taken together each behavior added to the level of suspicion and, in total,

created reasonable suspicion. The Commonwealth points to Adkins v.

Commonwealth, 96 S.W.3d 779, 788 (Ky. 2003), where this Court cited

nervousness as an appropriate factor in the reasonable suspicion analysis. To

support its argument that Appellant's behaviors of nervousness, glancing over

his shoulder, and blowing cigarette smoke create articulable suspicion, the

Commonwealth also cites cases from other jurisdictions: United States v.

Mason, 628 F.3d 123, 129 (4th Cir. 2010) (driver nervous); United States v ..

Holt, 777 F.3d 1234, 1257 (11th Cir. 2015) (driver nervous); Green v. State: 256

S.W.3d 456 (Tex. App. 2008) (outside vehicle, driver nervously glanced at it);

United States v. Christian, 43 F.3d 527, 530 (10th Cir. 1994) (driver had freshly

lit cigarette); State v. Franzen, 792 N.W.2d 5·33 (N.D. 2010) (driver had freshly

lit cigarette); and United States v. Neumann, 183 F.3d 753, 754, 756 (driver had

freshly lit cigarette).

Upon review, however, we are satisfied that these cases are not

comparable to the one now before us. Unlike Strange and Sanders, each of the

cited cases involved facts beyond the demeanor or behavior of the driver in the

vehicle that allowed a rational inference to be made that the driver was . .

11

engaging in criminal activity.4 In contrast, Officer Sorrell articulated nothing

about Appellant's.behaviors, individually or collectively, to connect him to

criminal behavior beyond what may be ordinarily expected of a driver stopped

for a traffic violation. Heightened nervousness is common among drivers

detain~d by a police officer for a traffic violation. See United States v. Wood,

106 F.3d 942, 948 (10th Cir. 1997). Sweating is a symptom of nervousness in

som~ people. Sorrell saw no indication that Appellant was intoxicated or

otherwise impaired. Moreover, he was fully cooperative and coherent. He

made no "furtive gestures" ,to indicate. he was trying to hide anything. The

Commonwealth hints that blowing smoke into the car's interior could have

been an attempt to mask an incriminating odor. However, even the trial court

was indifferent to the significance of that conduct. The trial court noted that

perhaps Appellant was being "courteous and not blowing smoke in the officer's

face. Or was he trying to cover up .. the smell of marijuana? Who knows?" No

marijuana or aromatic contraband was found.

4 For example, in Mason, the driver. did not pull over promptly and during that time spoke with the passenger; the officer encountered the extreme odor of air fresheners; the officer observed o:qly a single key on the driver's ring, who was traveling with a passenger ·on a known drug route from a source city; the driver and passenger gave conflicting answers about the purpose of their travel; and a newspaper in the backseat contradicted the driver and passenger's stories about where they stayed. In Holt, during the 2007 stop, the driver did not answer questions about where he was coming from and going to and the officer recognized the driver from his time working in a narcotics unit; during the 2010 stop, the driver offered only short, vague answers to the officer's questions and the driver and passenger provided inconsistent statements about their recent travel. And in Green, the driver had stopped in front of a known drug house, with someone walking from his truck back to the house; the driver had gotten out of and away from his truck when he was pulled over and was walkiI,lg toward the officer's car, and the driver, glancing nervously at his truck, initially did not comply with the qfficer's order to return to it.

12

Simply put, Appellant's behavior during the traffic stop as art~culated by

the officer on the scene and the prior charge information obtained during the

database search do not create a reasonable suspicion that Appellant was then

and there engaged in illegal behavior beyond the apparently obvious traffic

violations fqr which he was stopped. The dissent believes we have not

considered some circumstances that might be factored into the reasonable

suspicion calculatibn. We examined ail the facts relied upon by the officer as

the basis for his suspicion, as well as those cited by the trial court as

meaningful. The fact that Appellant was permissibly driving someone else's

uninsu:r~ed car does nothing to raise suspicion that criminal activity .was afoot

or that Appellant was transporting illegal drugs, which was the object of the

canine sniff search.

The dissent misconstrues the principle that "criminal history contributes

powerfully to the reasonable suspicion calculus." See United States v. Santos,

403 F.3d 1120, 1132 (10th Cir. 2005). As noted above, the officer claimed only

that Appellant had been previously charged with carrying a concealed weapon

' I and tr~ficking in marijuana; he admitted he had no knowledge of any prior

convictions. Mere charges do not constitute a "criminal history" upon which

one might reasonably suspect future criminal behavior. Even the prosecutor at

the suppression hearing, after mentioning Appellant's "criminal history,"

immediately corrected himself and said that Appellant had a "law enforcement

history." The Commonwealth never claims that the officer acted upon

knowledge of Appellant's criminal history because the record clearly shows he

13

did not. If Appellant even had a criminal history, it was not part of the

"calculus" used to determine reasonable suspicion in this case.

We are satisfied that even with the additional information obtained from

the online databases that Appellant had been previously charged with

trafficking in marijuana and carrying a concealed deadly weapon, the officer

had no reasonable suspicion to believe that Appellant was then and there

engaged in criminal activity beyond the traffic offenses for whibh he was

legitimately stopped. It follows that the dog sniff which followed was

unreasonable and· constitutionally impermissible. Evidence discovered during

the subsequent canine search must be suppressed as the product of an __,

unconstitutional seizure and should have been suppressed. Segura v. United

States, 468 U.S. 796, 804 (1984).

This opinion is not for Rakim Moberly. He has pleaded guilty and has

already served out his prison sentence for these crimes. We render this

opinion for the untold numbers of innocent Kentucky_citizens who have had

"criminal ch~ges" and may become nervous an_d sweaty and look around when

confronted by police at a traffic stop at night, and if smoking at the time, would

reasonably direct the smoke away from the officer. They have the right to live

their lives unfettered by police having no reasonable articulable suspicion to

interfere. The Commonwealth's position is tantamount to a, rule that says

those citizens have no ·Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable

searches and seizures. We reject that position.

Outcome: For the foregoi:rtg reasons, we reverse the Court of Appeals' decision and

remand the case to the Fayette Circuit Court for further proceedings consistent

with this· opinion.

Plaintiff's Experts:

Defendant's Experts:

Comments: